An exceptionally adaptable and hungry termite snuck into south Florida from the tropics, and is living in sections of Dania Beach, Fla. (Ft. Lauderdale metropolitan area, Broward County). These challenging “conehead termites” have tremendous potential for survival in a variety of structural and natural habitats across a broad geographic range, with decisive economic consequences if they become permanently established and spread.

An exceptionally adaptable and hungry termite snuck into south Florida from the tropics, and is living in sections of Dania Beach, Fla. (Ft. Lauderdale metropolitan area, Broward County). These challenging “conehead termites” have tremendous potential for survival in a variety of structural and natural habitats across a broad geographic range, with decisive economic consequences if they become permanently established and spread.

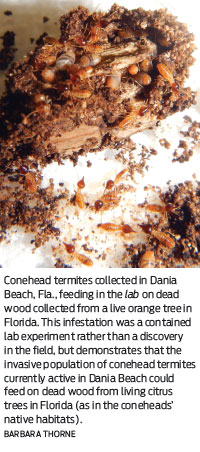

Coneheads have expansive tastes, eagerly consuming dead wood from live or dead trees (including citrus), shrubs, grasses, roots, structures and furniture, as well as cardboard and other paper products. These exotic termites were first discovered in Dania Beach in May 2001 but efforts to control it did not begin until nearly two years later (Scheffrahn et al. 2002, Scheffrahn et al. 2014). For decades USDA has categorized Nasutitermes corniger as a pest and intercepted it at ports; this is the first time that conehead termites have become established in the United States.

There is a sense of urgency to act now to halt and hopefully eradicate this exotic species because if it spreads further and becomes irreversibly established in the United States, it could become a powerfully damaging, expensive, obnoxious and permanent pest. Florida’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services is leading this effort, with support from local governments and residents; pest management professionals, trade associations and manufacturers; and scientists. Because my Ph.D. dissertation research focused on this termite species in Central America, I was asked to help with Florida’s containment/control/eradication effort. This article summarizes key aspects of conehead termite biology, along with treatment strategies and the rationale for the important — but challenging — goal of eradication.

Scientific/Common Name.

This species, scientific name Nasutitermes corniger, has the common name “conehead termite” because of the distinctive cone or teardrop-shaped head of the soldier caste. (Author’s note: This termite species was identified as Nasutitermes costalis when first discovered in Florida in 2001 [Scheffrahn et al. 2002], but it was subsequently synonymized as Nasutitermes corniger [Scheffrahn et al. 2005.]) It is broadly distributed in Central and South America as well as many islands in the Caribbean.

When this species was first discovered in Florida in 2001, it was called the “tree termite.” That nickname became confusing because most species of termites can live in and eat trees, and this exotic species often nests and feeds in places away from trees, including in structures. In short, “tree termite” did not help identify or differentiate this species. The Entomological Society of America recognizes “conehead termite” as the official common name for Nasutitermes corniger.

Identification.

Coneheads are quite different from other termite species in Florida or U.S. Three key things to look for:

Coneheads are quite different from other termite species in Florida or U.S. Three key things to look for:

1. Tunnels: Coneheads build extensive networks of narrow (usually half-inch wide or less) brown “tunnels” or termite highways on the sides of trees, houses, walls or almost any surface. Short sections of these foraging tunnels look similar to those built by subterranean termites, but conehead gallery networks are lengthy — trailing 40 feet or more up a tree trunk or over the eaves of a roof, for example. Often conehead foraging tunnels are the first sign of an infestation.

2. Coneheads: The soldier form of this termite has a distinctive, dark “conehead,” or teardrop-shaped head. If you break open one of the thin tunnels, little bugs, each shorter than grain of rice, may dash out, including the odd-looking “conehead” soldiers.

3. Nest: Older conehead termite colonies build conspicuous, dark brown nests, usually in the shape of a large ball or watermelon with a hard, bumpy surface. Nests may be on, in or by a tree, shrub or structure, or sometimes on open ground. Coneheads are not classic subterranean termites, but their nests (and foraging galleries) can extend underground.

Coneheads are Small.

Conehead termite workers and soldiers are small. Using the face of a penny as scale, conehead soldiers, from the tip of their pointy head to the end of their body, are about the length of the penny’s date stamp (e.g. 2014), or just longer than 1/8-inch. Most conehead termite workers are about that same length or just slightly longer. Conehead soldiers and workers are small compared to the size of most drywood termites in Florida, about the same size as subterranean termite workers and shorter than subterranean termite soldiers.

Conehead termite workers and soldiers are small. Using the face of a penny as scale, conehead soldiers, from the tip of their pointy head to the end of their body, are about the length of the penny’s date stamp (e.g. 2014), or just longer than 1/8-inch. Most conehead termite workers are about that same length or just slightly longer. Conehead soldiers and workers are small compared to the size of most drywood termites in Florida, about the same size as subterranean termite workers and shorter than subterranean termite soldiers.

Although conehead soldier and worker individuals are small compared to other termite species, conehead reproductives, including the winged swarmers, are larger than in most other species. The shiny blackish wings of conehead termites are about ½-inch in length; subterranean termite wings are considerably shorter.

Life Cycle.

As with most termites, winged female and male coneheads fly en masse during their swarm season. In south Florida, this mating flight typically occurs around twilight following the first heavy rain of the spring wet season (usually early May, but exact timing varies each year).

Before taking off, mature alates perch on the surface of their nest, and may climb on nearby grass blades or other substrates. Once a colony’s flight begins, alates launch in large numbers (up to tens of thousands emerging from a single large nest). Their departure forms “clouds” of shimmering charcoal-colored wings.

When alates land, they immediately begin searching for a mate and a nest site where they will initiate their family. The single flight of their lives now over, alates of both sexes lift their wings straight over their backs, causing each of the four wings to break off cleanly. Using chemical pheromones to find each other, males follow closely behind females, moving quickly to scoot into an opening in suitable wood and avoid being eaten by the hungry lizards, snakes, frogs, birds, ants, bats, etc., who delight in feasting on plump, nutritious alate termites.

The “Invisible” Phase.

After finding a mate and nest site, the new queen and king (or, in this species, there may be multiple queens and kings in one colony) sequester themselves in their new home. Both parents help rear the first set of brood, which always contains at least one or two conehead soldiers along with a group of “worker” offspring who will help with chores such as tending the nursery, harvesting wood and feeding colonymates, and — once the colony gets bigger — constructing foraging tunnels and a nest.

|

Why Do Conehead Termite Soldiers Have Cone-Shaped Heads? The head of conehead soldiers functions as a clever and highly effective squirt gun! Powerful muscles inside the head squeeze a gland that “shoots” a sticky spray from the tip of the solders’ pointed “nozzle” (formally termed the rostrum). Soldier coneheads are blind, but their sophisticated chemical senses enable them to detect and precisely aim at termite enemies such as ants, lizards or even termites from another colony. They can spray their gummy goo (chemically very close to pine sap) further than an inch. The soldiers’ spray is not poisonous, just sticky, causing ant antennae and legs to cling together and thereby incapacitates recipients of the viscous splash. The smell of the compound recruits other soldiers to the scene of the battle; if the provocation continues, they deploy their squirt guns to further cover the surface of their opponent. In addition to their key defensive role in a colony, conehead soldiers also serve as the lead “advance team” of scouts and organizers in their colony’s search for new food and foraging tunnel locations.

|

A tricky aspect of finding and eradicating coneheads is that young colonies remain completely hidden for years while they increase population size, feeding and traveling within dead wood. Conehead termites active now in Dania Beach, Fla., are descendants of the original infestation first discovered in 2001. During the years when there were reports of “eradication” of the exotic Nasutitermes corniger population in Dania Beach, healthy young colonies were in fact still present, but they evaded detection because they were in this early stage of growth and development, concealed within wood.

Coneheads’ “Big Reveal.”

Colonies concealed within wood eventually grow to a size empowering their “big reveal,” first by building visible tunnels, and ultimately a nest. The initial phase of construction creates a nest about the size of a tennis ball or softball, but healthy colonies rapidly expand their home such that a nest the size of a basketball (or even larger) may grow within a few months, and the same year may produce winged swarmers that disperse to found new colonies. Some nests remain hidden; in Dania Beach, a favorite site for coneheads is in the thick root ball of fakahatchee grasses, which can extend partially underground.

Gone But Not Forgotten.

Because there are no signs of coneheads during a young colony’s “invisible” phase (lasting three or four to possibly many more years), humans may glean a (false) sense of relief that the termites are gone. This devious twist of their biology means that even when we do not see conehead activity, and are tempted to conclude that the termites have been eradicated from an area, it is essential to continue careful inspections every six months or so for another decade.

Conspicuous tunnels and above-ground nests are the key aspects of N. corniger biology that render colonies more vulnerable to discovery and possible eradication. Diligent monitoring ensures that if any young, hidden colonies persist, those clandestine coneheads will be discovered and treated as soon as tunnels or a nest appear, thus preventing the infestation from reigniting due to lack of surveillance.

Diverse Reproductive Options.

Conehead termites take advantage of a wide variety of reproductive alternatives. In addition to the “normal” termite pattern of colonies founded by a single king and queen (monogamy), conehead capabilities include multiple queens, multiple kings, satellite nests, colony budding and nest relocation. Large colonies can produce more than 20,000 winged alates to disperse in one flight season. This plasticity makes Nasutitermes corniger exceptionally flexible, resilient and harboring the reproductive infrastructure for rapid colony growth (Thorne 1983, Roisin and Pasteels 1986, Adams and Atkinson 2007).

Do They Consume Living Plants?

As is true of many termites, N. corniger feed on dead tissues of live (as well as dead) plants, including fruit, commodity and native forest species. Coneheads as well as many other termite species (e.g. Coptotermes) damage live trees by carving out and consuming the inner dead heartwood. Trees die from the inside out as sapwood ages, cells die and then becomes heartwood. Tree heartwood, which comprises the majority of cross-sectional volume of a mature tree, is dead tissue that no longer conducts sap but is essential for structural support of living trees, and when weakened by termite damage, renders live trees vulnerable during storms (Osbrink et al. 1999).

Within its native, expansive range in the Neotropics, Nasutitermes corniger is known as a pest of fruit trees (including citrus) and other agricultural plants (e.g., sugar cane) (Snyder & Zetek 1934, Jutsum et al. 1981, Mill 1992, Constantino 2002). We are thus concerned that if this invasive species spreads much farther in Florida, commodity orchards and fields as well as forested areas and the Everglades’ natural landscape will be at risk. At that point options will default to continuous management and control initiatives because prospects for eradication of this invasive species are realistic only while it occupies a relatively small area.

How to Treat.

The good news is that once coneheads are found, there are effective ways to control them. Because the goal is to eradicate this species from the U.S., coneheads must be treated wherever they’re found — in a house, yard, park, overgrown lot, vegetation around bodies of water, etc. Site modification, especially removing dead plant material, helps reduce termite food and harborage, and enables termiticide to penetrate the soil.

Treatment involves an aggressive combination of nest removal and destruction teamed with application of conventional liquid termiticides. Fumigation is used only in extreme cases. By killing colonies and reducing overall population size in infested areas, alate production and dispersal will be reduced or eliminated, thus substantially slowing and hopefully halting expansion of the infested zone.

Containment.

A critical aspect of the conehead containment program is preventing the termite from “hitchhiking” to colonize another part of Florida or beyond. That possibility must be foiled by preventing transport of trees and shrubs, cut branches and wood debris, and wooden furniture or palettes out of the infested and surrounding locations. Young hidden colonies may be lurking within trees, shrubs or yard waste limbs. We can reduce the risk of coneheads expanding their range by not moving wood items out of currently infested and neighboring areas. People in Florida and other southern states also need to keep vigilant watch to quickly notice — and immediately treat — any new infestations.

Spread to Other States?

We don’t know if these termites will spread to other states and we hope the coneheads will be stopped before we find out. Many invasive animal and plant species have surprised scientists with how far and fast they have spread; exotic social insects (i.e., fire ants, Africanized bees and the Formosan termite) have proven especially formidable.

Coneheads are remarkably flexible in adapting to a wide variety of habitats, nest sites and acceptable foods; do not underestimate them. Their potential economic and ecological impacts would affect nearly every constituency — including homeowners, growers, businesses, institutions and natural areas such as the Everglades.

Coneheads are remarkably flexible in adapting to a wide variety of habitats, nest sites and acceptable foods; do not underestimate them. Their potential economic and ecological impacts would affect nearly every constituency — including homeowners, growers, businesses, institutions and natural areas such as the Everglades.

In contrast to construction practices and environmental conditions within this termite’s native range, most structures in Florida are built with wood as framing and other elements, and water is often plentiful with sprinkler systems, canals and lakes. Buildings are heated during winter chills. Although coneheads may adjust their behaviors and food preferences, seasonal cycle and growth rate to accommodate Floridian circumstances, they can clearly thrive in habitats like Dania Beach. How far and fast they may spread is anyone’s guess, and any such extrapolations are likely to be brashly disregarded by the adaptable coneheads. It seems prudent to make every effort to eradicate the invasive conehead termites while possible, and before we risk underestimating their impacts.

Goal is Eradication.

Eradication of this exotic termite population will be challenging, but the biology of this particular species differentiates it from other termites introduced into the United States and renders it more vulnerable to successful eradication if aggressive efforts are supported now. All other exotic termites that have invaded the United States remain hidden underground or in wood for their entire life cycle, making it impossible to find and treat each cryptic colony. In contrast, established conehead termite colonies reveal themselves by building conspicuous, visible nests and above-ground tunnels. Vigilant, repeated inspections can therefore locate active conehead termite colonies and effectively focus treatment strategies.

Conehead termites currently infest less than ½ square mile of residential, commercial and natural landscape area in Dania Beach, Fla. (part of the Ft. Lauderdale metropolitan area). Urgent, intensive actions now can halt the species before it spreads further and becomes irreversibly established in the United States as a powerfully damaging, expensive, obnoxious and permanent pest to structures, landscapes, agriculture and natural areas.

The author is a research professor and professor emerita at the University of Maryland and science adviser to Florida’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Selected References

Adams, E.S. and L. Atkinson. 2007. Queen fecundity and reproductive skew in the termite Nasutitermes corniger. Insectes Sociaux 55: 28-36.

Constantino, R. 2002. The pest termites of South America: taxonomy, distribution and status. Journal of Applied Entomology 126: 355-365.

Jutsum, A.R., J.M. Cherrett & M. Fisher. 1981. Interactions between the fauna of citrus trees in Trinidad and the ants Atta cephalotes and Azteca sp. Journal of Applied Ecology 18 (1): 187-195.

Mill, A.E. 1992. Termites as agricultural pests in Amazônia, Brazil. Outlook on Agriculture 21: 41-46.

Osbrink, W.L.A., W.D. Woodson, and A.R. Lax. 1999. Population of Formosan subterranean termite, Coptotermes formosanus (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae), established in living urban trees in New Orleans, Louisiana, Proceedings, 3rd International Conference on Urban Pests: 341-345.

Roisin, Y. and J.M. Pasteels. 1986. Reproductive mechanisms in termites: polycalism and polygyny in Nasutitermes polygynus (now synonymized with N. corniger) and N. costalis (now synonymized with N. corniger). Insectes Sociaux 33: 149-167.

Scheffrahn, R.H., B.J. Cabrera, W.H. Kern Jr., & N-Y. Su. 2002. Nasutitermes costalis (Isoptera: Termitidae) in Florida: first record of a non-endemic establishment of a higher termite. Florida Entomologist 85(1): 273-275.

Scheffrahn, R.H., H.H. Hochmair, W.H. Kern Jr., J. Warner, J. Krecek, B. Maharajh, B.J. Cabrera, and R.B. Hickman. 2014. Targeted elimination of the exotic termite, Nasutitermes corniger (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae), from infested tracts in southeastern Florida. International Journal of Pest Management 60, Issue 1. Online only: DOI: 10.1080/09670874.2014.882528.

Scheffrahn, R.H., J. Krecek, A.L. Szalanski, J.W. Austin 2005. Synonomy of Neotropical Arboreal Termites Nasutitermes corniger and N. costalis (Isoptera: Termitidae: Nasutitermitinae), with Evidence from Morphology, Genetics, and Biogeography. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 98(3): 273-281.

Snyder, T.E. & J. Zetek. 1934. The termite fauna of the Canal Zone, Panama, and its economic significance. In: Kofoid, C.A. (editor) Termites and Termite Control, University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif. pp. 342-346.

Thorne, B.L. 1983. Alate production and sex ratio in the Neotropical termite Nasutitermes corniger. Oecologia 58(1): 103-109.

Explore the February 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- SiteOne Hosts 2024 Women in Green Industry Conference

- Veseris Celebrates Grand Reopening of the Miami ProCenter

- Rollins' 2024 Second Quarters Revenues up 8.7 Percent YOY

- Fleetio Go Fleet Maintenance App Now Available in Spanish

- German Cockroach Control Mythbusting

- Total Pest Control Acquires Target Pest Control

- NPMA Workforce Development Shares Hiring Updates

- Certus Acquires Jarrod's Pest Control