Certain pests move into structures in the fall in response to weather and shorter days signaling the approach of winter. Pests also move inside when their outside conditions become less than desirable: too hot, too dry, too wet, too crowded or when there’s a drop in available food. Some outside arthropods are carried in on plants or firewood, or are attracted to lights, and don’t want to be inside at all. But when a customer sees dozens of stink bugs or cluster flies in the living room, he wants to know what they are, whether they bite or spread disease, and maybe most importantly, whether they are going to reproduce and infest his home.

Seasonal invaders usually are only temporary nuisance pests indoors. Most either go into hiding to wait out the winter and aren’t seen for months, or they die fairly soon in the drier indoor conditions. In unusual and exceptional circumstances some invading insects may be able to survive and even reproduce, if only on a short-term basis. To pull this off, the invaders will need high moisture levels, suitable temperatures and a reliable food source.

Overwintering insects will move back outside to reproduce. Most fall invaders that move in when the weather gets cooler are plant- or crop-feeding insects so it follows that they won’t have a food source once inside. They’re not interested in feeding or breeding anyway since they are just looking to wait out the winter in a state of semi-hibernation in a warm, protected site. These overwintering pests can gather and enter in large numbers, scaring customers. They hide in attics and cracks and crevices and may not be seen again until spring or on warm, sunny days in winter. In early spring they move back outside to their host plants where they mate and lay eggs. These overwintering insects don’t feed or reproduce inside but some exude defensive fluids that can stain fabrics and some can cause asthmatic or allergic reactions in sensitive individuals.

This group includes brown marmorated stink bugs, boxelder bugs, elm leaf beetles, western conifer seed bugs and kudzu bugs. Cluster flies, multicolored Asian lady beetles and paper wasp queens are overwintering insects that are not plant feeders.

Invaders requiring high moisture don’t survive to reproduce. Perimeter pests that enter structures due to changes in outside conditions are more often found already dead due to a lack of moisture. These moisture-loving pests are normally found in dark, damp areas around foundations where they hide in moist soil, mulch and leaf litter, usually feeding on decaying vegetation. They don’t want to be inside, they were just hoping to find better conditions. Unless a site is very damp, most of these invaders don’t have much of a chance of surviving more than a few days. The odds of finding the right conditions for reproduction indoors are slim although possible, depending on the species.

This high-moisture group includes pillbugs, sowbugs, earwigs, millipedes, springtails, field crickets, camel crickets and wood cockroaches.

Some invaders can reproduce outside or inside. The seasonal invaders that can survive indoors are generally those that are omnivorous, feeding on a variety of foods that can be found inside, including garbage, pet food, dead insects or animal carcasses. Or, they are predators on live insects and other arthropods found inside. Some entering accidentally are adapted to indoor conditions and can go on to become household pests requiring control.

Insects and arthropods that would be capable of moving in, surviving and reproducing at any time of year are often called “peridomestic,” meaning they can live and reproduce either outdoors or indoors and even may move between the two. In warm regions, these pests may remain outside year round, while in colder regions they may seek seasonal shelter. These pests are common outside around foundations but also can establish themselves inside if they can find a suitable site.

This group of invaders that could survive and reproduce indoors include peridomestic cockroaches such as the American cockroach, oriental cockroach, Australian cockroach and other southern species. Other examples of perimeter invaders that can become established indoors are the house cricket and the house centipede. Note that the word “house” in their common name is a clue. Many of our common household pests spend part of the year outside and part inside. Carpet beetles, for example, will feed and mate outside but then may move inside to lay their eggs. Many outdoor ants species also can establish indoor nests, many outdoor spiders and scorpions also will live and breed in indoor spaces, and nuisance flies will enter and breed indoors if decaying or overripe food is available for the larvae.

The authors are well-known industry consultants and co-owners of Pinto & Associates.

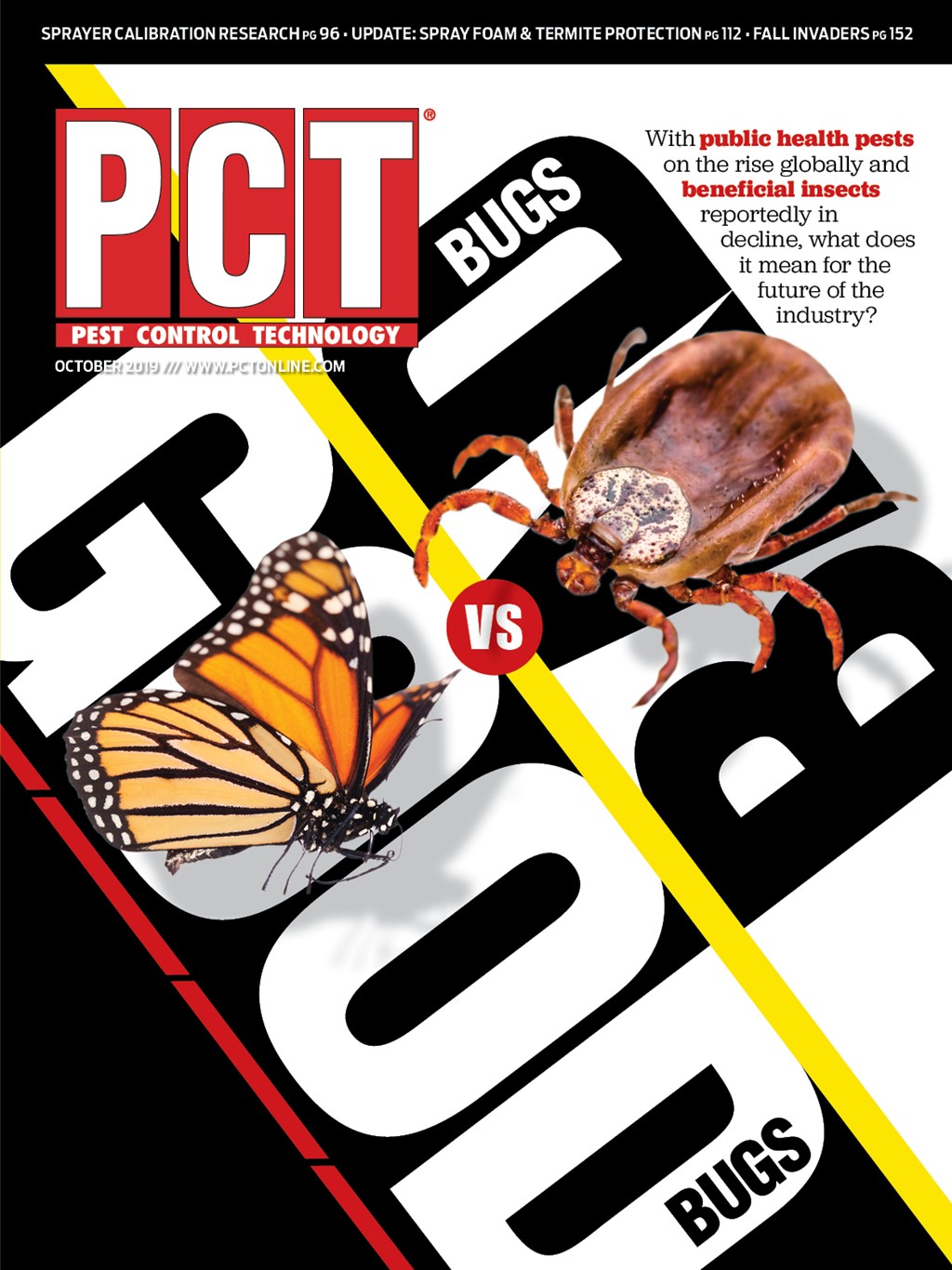

Explore the October 2019 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- SiteOne Hosts 2024 Women in Green Industry Conference

- Veseris Celebrates Grand Reopening of the Miami ProCenter

- Rollins' 2024 Second Quarters Revenues up 8.7 Percent YOY

- Fleetio Go Fleet Maintenance App Now Available in Spanish

- German Cockroach Control Mythbusting

- Total Pest Control Acquires Target Pest Control

- NPMA Workforce Development Shares Hiring Updates

- Certus Acquires Jarrod's Pest Control