The great dualism of so many arthropod species is that while they may live in our midst as completely benign entities most of the time, now and again they can’t help but be in the wrong place at the wrong moment and are instantly transformed into undesirable aliens that must be controlled. A large part of their situation-specific pest status is due to the expectation of total indoor sterility that is endemic to Western societies and constitutes one of the primary confounding obstacles to the structural IPM paradigm.

The great dualism of so many arthropod species is that while they may live in our midst as completely benign entities most of the time, now and again they can’t help but be in the wrong place at the wrong moment and are instantly transformed into undesirable aliens that must be controlled. A large part of their situation-specific pest status is due to the expectation of total indoor sterility that is endemic to Western societies and constitutes one of the primary confounding obstacles to the structural IPM paradigm.

One of the most common manifestations of this rule is the reaction of so many building occupants to a small spider roaming on the wall or a lost wasp buzzing against the inside of a windowpane. A far cry from the epic suffering inflicted on humanity by malaria mosquitoes or Chagas disease-infected conenose bugs, both spider and wasp are relatively innocuous to us in the great scheme of things, but typically provoke a substantial alarm reaction that ends in the unfortunate creature’s demise.

Nevertheless, the extraordinarily intricate world of our built environment creates a broad gradient of consequences when normally insignificant critters wander into our realm. Totally apart from any actual risk posed by their venom, the same spider or wasp is perfectly capable of killing one or more humans in the blink of an eye if either makes a sudden, startling appearance inside a rapidly moving automobile. At the extreme end of this spectrum are outcomes catastrophic beyond belief that stem from the same type of humble, unremarkable behavior. The entomological epitome of this “for want of a nail” syndrome was the short, tragic flight of Birgenair Flight 301 in 1996. The incident was analyzed and re-enacted in The Plane That Wouldn’t Talk episode of Air Crash Investigation, a television series produced by National Geographic.

Departing from an airport in the Dominican Republic after 25 days of inactivity, the Boeing 757 plunged into the ocean less than five minutes after takeoff, killing all 189 people aboard. It was the worst accident involving a type of jet that still has one of the best safety records of any modern commercial aircraft. Recovered from the seabed by a U.S. Navy salvage team, the plane’s data recorders revealed a terrifying ordeal in the cockpit as the flight crew struggled to comprehend an unrelenting, intensifying sequence of radically conflicting airspeed readings and related warning signals. Acting on his instrument’s insistence (and the autopilot’s automatic concurrence) that the plane was flying dangerously fast, the captain — a seasoned veteran who had logged thousands of hours in 757s — allowed the computer to reduce power, then compounded the action manually, ignoring intense vibrations indicating that the plane was in fact moving far too slowly and that a stall was imminent.

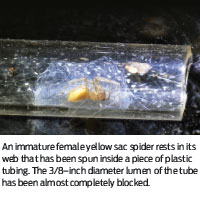

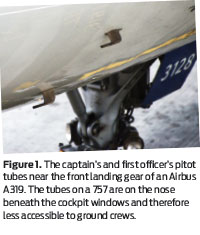

It proved to be a terrible mistake. As pieced together by investigators, the captain’s airspeed gauge had been transmitting faulty readings from its pitot (pronounced PEE-toe) tube, a cylindrical sensor mounted on the plane’s exterior that measures the pressure of the airstream entering the tube’s narrow opening (Figure 1). Because this hole is so small, about half an inch in diameter, pilots the world over know it is prone to being blocked by ice, debris or living creatures — “bugged and plugged” as the aeronautical saying goes. For this reason, it is considered standard practice to always check the pitot tubes (there is more than one on large commercial jets) for obstructions prior to flight. Heating elements are incorporated to deal with icing, but the universally accepted way to prevent the bug issue is to shield the tubes with fitted covers or plugs if the craft is on the ground for any extended period. These specialized protective devices — IPM for tube-dwelling arthropods, as it were — are marked by brightly colored streamers to remind everybody that they need to be removed prior to flight. Operators of smaller, private aircraft have been known to use a rubber chicken (or similarly outrageous implement) for pitot tube security.

It proved to be a terrible mistake. As pieced together by investigators, the captain’s airspeed gauge had been transmitting faulty readings from its pitot (pronounced PEE-toe) tube, a cylindrical sensor mounted on the plane’s exterior that measures the pressure of the airstream entering the tube’s narrow opening (Figure 1). Because this hole is so small, about half an inch in diameter, pilots the world over know it is prone to being blocked by ice, debris or living creatures — “bugged and plugged” as the aeronautical saying goes. For this reason, it is considered standard practice to always check the pitot tubes (there is more than one on large commercial jets) for obstructions prior to flight. Heating elements are incorporated to deal with icing, but the universally accepted way to prevent the bug issue is to shield the tubes with fitted covers or plugs if the craft is on the ground for any extended period. These specialized protective devices — IPM for tube-dwelling arthropods, as it were — are marked by brightly colored streamers to remind everybody that they need to be removed prior to flight. Operators of smaller, private aircraft have been known to use a rubber chicken (or similarly outrageous implement) for pitot tube security.

That a major commercial jet should sit on the tarmac for more than three weeks is unusual by itself, but the struggling discount charter firm of Birgenair simply didn’t have the passengers to justify the expense of flying it. What violated international protocol was that no covers were available for the 757’s pitot tubes, no mechanic or other employee drew attention to their absence and thus the orifices remained open for the duration of the plane’s downtime. Three weeks was more than enough for a variety of living things to completely occlude a half-inch hole.

Case of Mistaken Identity?

Flight 301’s recorders solved the primary mystery of the plane’s demise, but since no pitot tube was ever recovered from the wreckage, the actual offender remains a matter of conjecture. From conversations with ground crew at the Dominican airport, the likely culprit was deemed to be some sort of solitary wasp or bee that uses mud to seal its nests. There are dozens of potential species that fit the bill, but somehow attention focused on one of the largest and showiest members of the airport’s insect fauna, Sceliphron caementarium, the familiar black and yellow mud dauber found throughout most of North and Central America, including the Caribbean. To this day, cast in stone by the Internet, this particular wasp is associated with the Birgenair disaster.

Flight 301’s recorders solved the primary mystery of the plane’s demise, but since no pitot tube was ever recovered from the wreckage, the actual offender remains a matter of conjecture. From conversations with ground crew at the Dominican airport, the likely culprit was deemed to be some sort of solitary wasp or bee that uses mud to seal its nests. There are dozens of potential species that fit the bill, but somehow attention focused on one of the largest and showiest members of the airport’s insect fauna, Sceliphron caementarium, the familiar black and yellow mud dauber found throughout most of North and Central America, including the Caribbean. To this day, cast in stone by the Internet, this particular wasp is associated with the Birgenair disaster.

The diagnosis is almost certainly wrong. S. caementarium builds its large, lumpy nests in sheltered locations, but never in the narrow confines of a pre-existing tunnel with the slim diameter of a pitot tube (Figure 2). Consider, for example, Karl Krombein’s unparalleled text, Trap-Nesting Wasps and Bees (Smithsonian Press, 1967). In more than a decade of investigating the contents of more than 3,400 trap-nests with holes ranging from 1/8 to 1/2 inch that lured in 75 wasp species from New York to Florida, not a single Sceliphron was ever recorded. He did, however, attract several species in the genus Trypoxylon. Most members of this group are known as “keyhole wasps” for their habit of nesting in pre-existing tunnels (including abandoned Sceliphron nests) and sealing the finished nest with a mud plug — definitely among the candidates for the Dominican pitot tube perpetrator (Figure 3).

The generic designation, however, is confounded by an atypically large and behaviorally distinct species that is widespread in eastern North America, T. politum, which fabricates striking mud nests attached to sheltered surfaces that consist of a cluster of elongate, parallel cylinders. It is thus known as the “organ pipe mud dauber.” Although, like Sceliphron, the odds of this specific wasp utilizing a pitot tube for its nest would be vanishingly small, the National Geographic editors selected stock footage of T. politum for their Flight 301 story, probably to emphasize the tubular nature of mud dauber nests!

The generic designation, however, is confounded by an atypically large and behaviorally distinct species that is widespread in eastern North America, T. politum, which fabricates striking mud nests attached to sheltered surfaces that consist of a cluster of elongate, parallel cylinders. It is thus known as the “organ pipe mud dauber.” Although, like Sceliphron, the odds of this specific wasp utilizing a pitot tube for its nest would be vanishingly small, the National Geographic editors selected stock footage of T. politum for their Flight 301 story, probably to emphasize the tubular nature of mud dauber nests!

It is an extended example of a familiar “hierarchy of function,” in which pest control or entomology is considered to have a much lower index of factual concern and respect in relation to disciplines such as engineering. The aspects of the air crash investigation dealing with mechanical issues were painstaking, detailed and sophisticated. But when it came to identifying the ultimate cause of the disaster, a conclusion that one would think would be of interest to anybody, the authorities were content with generalities. Apparently, nobody even considered putting out trap-nests (i.e., holes drilled in a block of wood) with Boeing 757 pitot tube dimensions around the airport to see what actually populated them, a first step that would have been suggested by any grad student specializing in Hymenoptera.

The legacy of Flight 301 was considerable. A blocked pitot tube exercise (not quite a Kobayashi Maru scenario, but exceptionally harrowing nonetheless) was added to airline pilot simulator training by Federal Aviation Administration mandate, as well as a change in Boeing cockpit warning signals to make them more incisive and less discordant.

Wasp nest-compromised pitot tubes on passenger jets continue to wreak their mischief around the world on an occasional basis, but due to the increased awareness of the operational symptoms — that preventive, IPM philosophy again — disasters have been averted and the accounts remain buried in the aviation literature. For example, in a three-month period in 2006, Qantas had five pitot system failures due to “wasp infestations” on jets departing from Brisbane. On one aborted flight, six of the aircraft’s eight tires burst because of overheating when the crew slammed on the brakes during takeoff.

Silken Monkey Wrenches.

The vulnerability of such a critical piece of equipment as an airplane pitot tube is disconcerting, made all the more so because it is merely a subset of a much broader pest issue involving all sorts of narrow mechanical apertures. As it turns out, there is another famous tube-blocker in the structural environment that commonly produces malfunctions in a far wider array of items, and in a far briefer period of time, than any wasp possibly could. Rather than a nest with mud partitions that might take days to complete, yellow sac spiders in the genus Cheiracanthium fashion their cocoon-like sanctuaries (for both shelter and egg protection) out of densely woven silk in less than an hour. They are notorious throughout numerous industries.

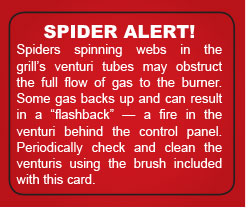

For example, in the 1960s, the Washington Gas Light Company (WGLC) realized the silken cases were causing significant service problems by plugging the burner orifices and pilot aeration openings of air conditioners and heaters in the District of Columbia metropolitan area. A 1965 report from the company’s Research and Utilization Laboratory observed that “these webs display a remarkable tenacity to adhere to the metal surfaces, and usually extensive dismantling is required in order to remove the obstruction.”

The report also cited a western utility that had estimated annual service costs directly attributable to spiders as conservatively ranging from $28,000 to $47,000. Data gathered by WGLC service personnel during their 1968-71 spring inspections of more than 8,000 residential air conditioners indicated that up to 30 percent of the units were affected to the point where operation of the appliance was compromised. All attempts at the time to remedy the issue through engineering means, including fiber optics to introduce light into the gas manifold, use of slippery coatings, screening and various chemical repellents, eventually ended in failure.

Many utilities throughout the country have reported similar findings, and as the popularity of outdoor gas grills soared after their invention in the 1960s, so did the incidence of malfunctions due to webbing in the brass spud or hood orifices, or deeper into the system in the venturi tubes. Backed-up gas in a supply tube can ignite, resulting in appliance damage or human injury. One of the many seminar props of pest management industry legend Austin Frishman was a bright red card and small brush supplied to all customers of a gas grill manufacturer. Entitled SPIDER ALERT!, the card read:

A similar warning is included in the user manuals of several brands of grills. Other types of equipment susceptible to Cheiracanthium-induced operating failures include water and space heaters, furnaces, dryers, ranges, smoke detectors and various types of infrared sensors (such as used in motion detectors). During the 2012 presidential election, a voting machine in the Massachusetts town of Rehoboth malfunctioned during the morning rush period due to a “spider’s web” that blocked the machine’s optical scanner, despite the fact that the Town Clerk had tested the equipment a week previously.

But nothing so far equals the media impact of the 2011 recall of 65,916 Mazda automobiles in the United States, Canada, Puerto Rico and Mexico due to a widespread Cheiracanthium infestation in fuel system ventilation hoses. Mazda’s report to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration invoked an escalating cascade of potential consequences:

“A certain type of spider may weave a web in the evaporative canister vent line and this may cause a restriction in the line. If this occurs, the fuel tank pressure may become excessively negative when the emission control system works to purge the vapors from the canister. As the canister is purged repeatedly during normal operation, the stress on the fuel tank may eventually result in a crack, potentially leading to fuel leakage and an increased risk of fire.”

Soon afterwards, a similar problem was identified in Honda Accords. Honda did not feel the matter warranted a recall, but alerted its dealers and issued a detailed technical service bulletin instructing mechanics how to prevent the situation. Both Mazda and Honda quickly adapted a small spring to function as a protective barrier at the hose port where the spiders were entering. But Cheiracanthium’s relationship with the auto industry apparently runs deep. In 2013, Toyota initiated the largest spider-themed recall so far, targeting 870,000 vehicles in three product lines that were susceptible to web blockages in air conditioning condenser drain tubes. This time, the unholy sequence of events included water dripping down onto an airbag control module, leading to a short circuit and — in the worst case scenario, which actually occurred at least three times — explosive deployment of the airbag without warning.

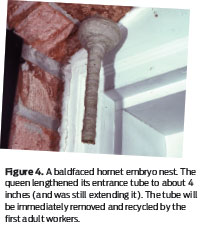

As a final postscript to the sac spider part of this story, it must be noted that these arachnids throw silken monkey wrenches into the lives of other creatures as well. Many years ago I observed the progress of a baldfaced hornet embryo nest built under the eaves of a Maryland house. As is typical with this species, the foundress queen prolonged the outer envelope into a cylindrical vestibule about two inches long and half an inch wide — essentially the diameter of an airplane’s pitot tube — at the point when her oldest larvae pupated (Figure 4).

As a final postscript to the sac spider part of this story, it must be noted that these arachnids throw silken monkey wrenches into the lives of other creatures as well. Many years ago I observed the progress of a baldfaced hornet embryo nest built under the eaves of a Maryland house. As is typical with this species, the foundress queen prolonged the outer envelope into a cylindrical vestibule about two inches long and half an inch wide — essentially the diameter of an airplane’s pitot tube — at the point when her oldest larvae pupated (Figure 4).

One day, just prior to the first adult worker emergence, I was surprised to find the queen lingering just outside the nest, at a time when she should have been spending most of her time inside, appressed on the capped cells to thermoregulate her brood. It turned out that the entrance tube was occupied by a Cheiracanthium inclusum female, her body and surrounding webbing totally occluding it for most of its length.

The spider was markedly gravid and was almost certainly preparing to deposit her egg mass. Facing outward in an impregnable position, she had effectively excluded the queen and was thus in the process of exterminating the incipient colony. Since there have been only a very few field biologists in the history of the world who have systematically examined young baldfaced hornet nests, it is impossible to know just how frequently this sort of thing occurs. If it is indeed a significant mortality factor, rather than the human cultural responses of instruction manuals or training exercises, baldfaced hornets are already dealing with the issue the old-fashioned way through the mechanism of differential gene selection for behavioral countermeasures.

Conclusion.

For most students of anthropogenic habitats, the ecological guild of mud wasps and sac spiders is probably relevant mainly as an offbeat illustration of chaos theory, which studies the progression of events within complex, dynamic systems that are highly sensitive to small perturbations in initial conditions (the so-called “butterfly effect”).

But for our purposes, I can’t think of a more vivid example of the incalculable number of ways that animals can earn pest status, the vast diversity of negative consequences as a result of arthropod interference in human affairs, and why the IPM ideal of designed-in prevention combined with informed, routine inspection is the only sustainable management response.

This article has been excerpted from a forthcoming book by the author on the theory, history and practice of IPM in buildings.

The opinions expressed herein are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA). Dr. Greene is entomologist and national IPM coordinator for the GSA’s Public Building Service in Washington, D.C. He can be reached via e-mail at agreene@giemedia.com.

More On Mazda Spider Recal

Last month, Mazda recalled some of its cars to fix a problem with spiders getting inside and wreaking havoc. The latest recall involves 42,000 Mazda6 midsize sedans from the 2010-12 model years, and equipped with the 2.5-liter, four-cylinder engine, the LA Times reports.

To read more, click here.

Explore the May 2014 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find you next story to read.

Latest from Pest Control Technology

- Viking Pest Control Organizes a Charity Bike Build for Local Families

- Gaining Control of Structure-Infesting Carpenter Ants

- Big Blue Bug’s Brian Goldman Receives Rhode Island Small Business Person of the Year Award

- UF Researchers Examine How Much Bait it Takes to Eliminate a Subterranean Termite Colony

- Women in Pest Control Group Continues to Grow, Provide Opportunities in the Industry

- NPMA Announces Results of 2024-2025 Board of Directors Election

- Massey Services Acquires Orange Environmental Services

- Hawx Pest Control Wins Bronze Stevie Award for Sustainability